The Indian criminal justice system is currently undergoing a massive transformation. Most importantly, the shift from the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) to the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) has changed how police register cases.

Additionally, a landmark 2026 Supreme Court ruling has now clarified the Section 173 BNSS preliminary inquiry process. This decision establishes a strict 14-day window for police to vet certain complaints. In this post, we will explore how this ruling impacts FIR registration and legal practice in India.

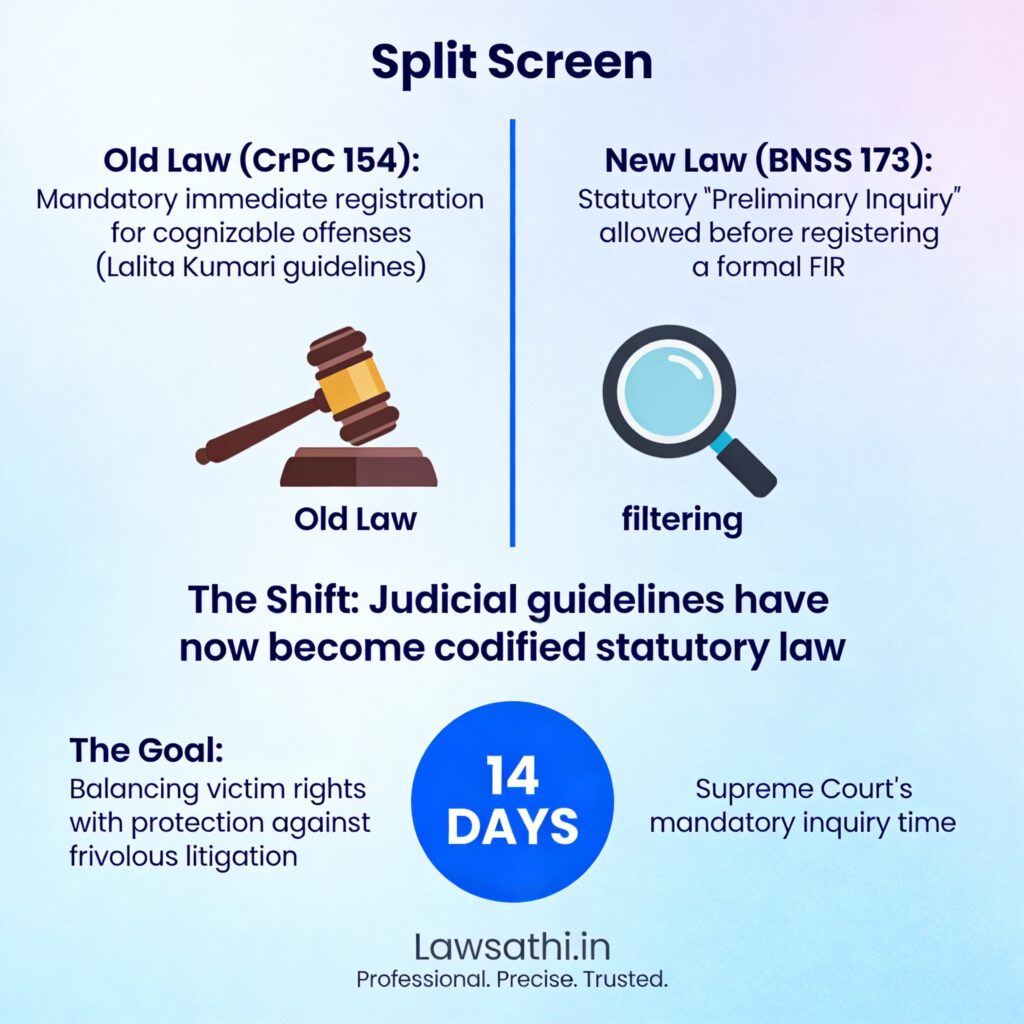

Introduction: The Shift from CrPC 154 to BNSS 173

For decades, Section 154 of the CrPC dictated the FIR registration procedure in India. Under the old law, police had to register an FIR immediately if a complaint disclosed a cognizable offense.

However, the new BNSS 173 introduces a fresh procedural layer. Specifically, it allows for a preliminary inquiry before a formal case is filed. Therefore, lawyers must adjust their strategies to account for this statutory “filtering” stage.

The Evolution of FIR Registration Laws

In the past, the Supreme Court mandated immediate FIR registration to prevent police inaction. For example, the Lalita Kumari guidelines set the standard for years. Under the new regime, Section 173 of the BNSS formalizes these judicial guidelines.

Furthermore, this change aims to balance the rights of victims with the need to prevent frivolous litigation. Consequently, the 2026 judicial clarification is vital for every criminal defense and prosecution lawyer in the country.

Why the 2026 SC Clarification Matters

Recent judicial reviews highlight how Section 173 affects constitutional rights. For instance, the Court recently addressed whether the inquiry period could be extended indefinitely.

As a result, the 2026 ruling provides a clear roadmap for trial courts and high courts. It ensures that the police do not use the inquiry period as a tool for harassment. Moreover, lawyers now have a definitive timeline to hold the authorities accountable.

Understanding the 2026 SC Ruling: Context and Conflict

The 2026 ruling arose from a significant legal conflict regarding police discretion. The court had to decide if the word “may” in Section 173(3) gave police unlimited time.

Specifically, this debate started following the case of Imran Pratapgadhi v. State of Gujarat. In that instance, the conflict centered on whether an inquiry was mandatory or optional. The Court ultimately ruled that Section 173(3) is a specific exception to general FIR registration rules.

Reconciling Section 173 with Article 21

The Supreme Court emphasized that liberty is a fundamental right. Therefore, a Section 173 BNSS preliminary inquiry must respect the protections under Article 21.

If the police delay an FIR without cause, they violate the complainant’s right to justice. Conversely, if they register a false FIR, they violate the accused’s right to reputation. The 2026 ruling bridges this gap by enforcing strict procedural safeguards during the pre-FIR stage.

Protecting Free Speech and Personal Liberty

Furthermore, the Court linked the inquiry process to Article 19. It noted that cases involving speech often require a “filter” to prevent the suppression of dissent.

In fact, according to research on filtering frivolity, an inquiry is “always appropriate” when artistic or political expression is involved. Consequently, the 14-day window acts as a shield against malicious prosecutions.

Decoding the 14-Day Timeline for Preliminary Inquiry

The most critical part of the 2026 ruling is the mandatory timeline. Section 173(3)(i) of the BNSS states that an inquiry must be completed within 14 days.

Most importantly, this period is not a mere suggestion. Instead, it is a legal mandate that the police must follow strictly. For instance, if an investigating officer takes 20 days, the entire inquiry process might be deemed illegal by a Magistrate.

When does the 14-day clock apply?

The 14-day timeline applies specifically to offenses punishable by 3 to 7 years of imprisonment. Additionally, the police must obtain prior permission from a senior official.

This official must not be below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DySP). Without this DySP approval, the inquiry has no legal standing. This hierarchy ensures that senior officials supervise the decision to delay an FIR registration.

Exceptions for Complex Cases

However, the legal community often asks if complex cases allow for extensions. The Court clarified that the 14-day limit remains the standard even for financial or matrimonial disputes.

In fact, procedural discussions on BNSS suggest that any extension requires documented reasons. If the police fail to provide these reasons, the inquiry becomes vulnerable to a legal challenge.

From Lalita Kumari to BNSS: The Legal Transition

Interestingly, the Section 173 BNSS preliminary inquiry has its roots in the Lalita Kumari vs. Govt. of UP judgment. In that case, the SC created the concept of a “preliminary inquiry” for specific categories.

These included matrimonial, commercial, and corruption cases. Now, the BNSS has codified these categories into statutory law. As a result, this transition means that an inquiry is no longer just a judicial suggestion. Instead, it is a legal right.

Narrowing the Scope of Inquiries

Under the old law, the scope of a preliminary inquiry was often broad. Now, Section 173(3) limits this scope significantly.

The police can only conduct an inquiry to see if a prima facie case exists. They cannot use this time to test the absolute veracity of the evidence. Therefore, the inquiry is a “filter for cognizable offenses” rather than a mini-trial.

Statutory Recognition vs. Judicial Creation

Previously, lawyers relied on case law to demand or challenge inquiries. Today, they can cite the difference between Section 154 CrPC and Section 173 BNSS directly from the statute.

This statutory recognition provides more certainty to the legal process. In other words, the BNSS provides a clearer framework for both the police and citizens to follow.

Procedural Safeguards for Accused and Complainants

Transparency is the cornerstone of the updated Section 173 BNSS preliminary inquiry rules. One major safeguard is the requirement to inform the complainant.

Specifically, the police must notify the informant of the inquiry outcome within a very short window. Usually, this must happen within 24 hours. This ensures that the complainant knows whether the police will register an FIR or close the matter.

Police Accountability and Documentation

Moreover, every step of the inquiry must be documented. The DYSP must record the “nature and gravity” of the offense before authorizing the inquiry.

If the police decide not to file an FIR, they must provide a written report. This documentation serves as a vital tool for lawyers. For example, if a lawyer finds gaps in the inquiry report, they can challenge the decision under Section 175 of the BNSS.

Remedies for Non-Compliance

What happens if the police ignore the 14-day rule? In such cases, the BNSS provides specific remedies.

First, the complainant can approach the Superintendent of Police under Section 173(4). Second, they can petition a Magistrate for a directed investigation. Most importantly, the 2026 ruling confirms that courts can quash delayed inquiries that lack proper authorization.

Impact on Legal Practice: What Lawyers Need to Change

Modern criminal litigation requires a deep understanding of BNSS timelines. Consequently, defense lawyers should monitor whether the 14-day window was exceeded.

If the police failed to register an FIR within 14 days, this delay is significant. It can be used as a ground for bail. Furthermore, it can even serve as a basis for quashing the FIR in the High Court.

Strategies for Prosecution and Complainants

On the other hand, lawyers for complainants must be proactive. First, you should ensure that all complaints are digitally timestamped. This sets the 14-day clock in motion officially.

Second, you should actively follow up with the DySP’s office to confirm the inquiry status. According to legal experts at Live Law, early intervention is the best way to prevent police inaction.

Using Digital Evidence and Trackers

Digital evidence is now more important than ever. Because the BNSS emphasizes digital records, lawyers should keep copies of e-FIRs and digital receipts.

These timestamps prove when the communication reached the police station. In fact, many successful lawyers are now using legal tech tools to track these statutory deadlines. This prevents missing the window to file a Section 175 application before the Magistrate.

Conclusion: A Step Toward Transparency or Procedural Delay?

The 2026 Supreme Court ruling on the Section 173 BNSS preliminary inquiry is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it protects citizens from the stigma of false FIRs.

On the other hand, it adds a 14-day waiting period for victims of crime. However, the Court’s insistence on a strict timeline ensures that this delay does not become indefinite. Ultimately, the ruling promotes police accountability while upholding constitutional values.

By understanding these nuances, lawyers can better navigate the complexities of the BNSS. Whether you are defending a client or seeking justice for a victim, the 14-day window is now your most important deadline.

Stay updated with judicial developments to ensure your practice remains compliant. Book a demo today with LawSathi AI to see how our automated timeline tracking keeps your practice efficient.