The legal battle over communal land rights has taken a significant turn. Specifically, the Adani grazing land Supreme Court case has entered a new phase. Recently, the apex court stayed a Gujarat High Court direction. This direction concerned 108 hectares of village land.

This dispute centers on the Mundra region of Kutch. It pits the expansion of Adani Ports and SEZ (APSEZ) against local villagers. These villagers are fighting for their primary grazing rights.

The Origin of the Kutch Land Dispute

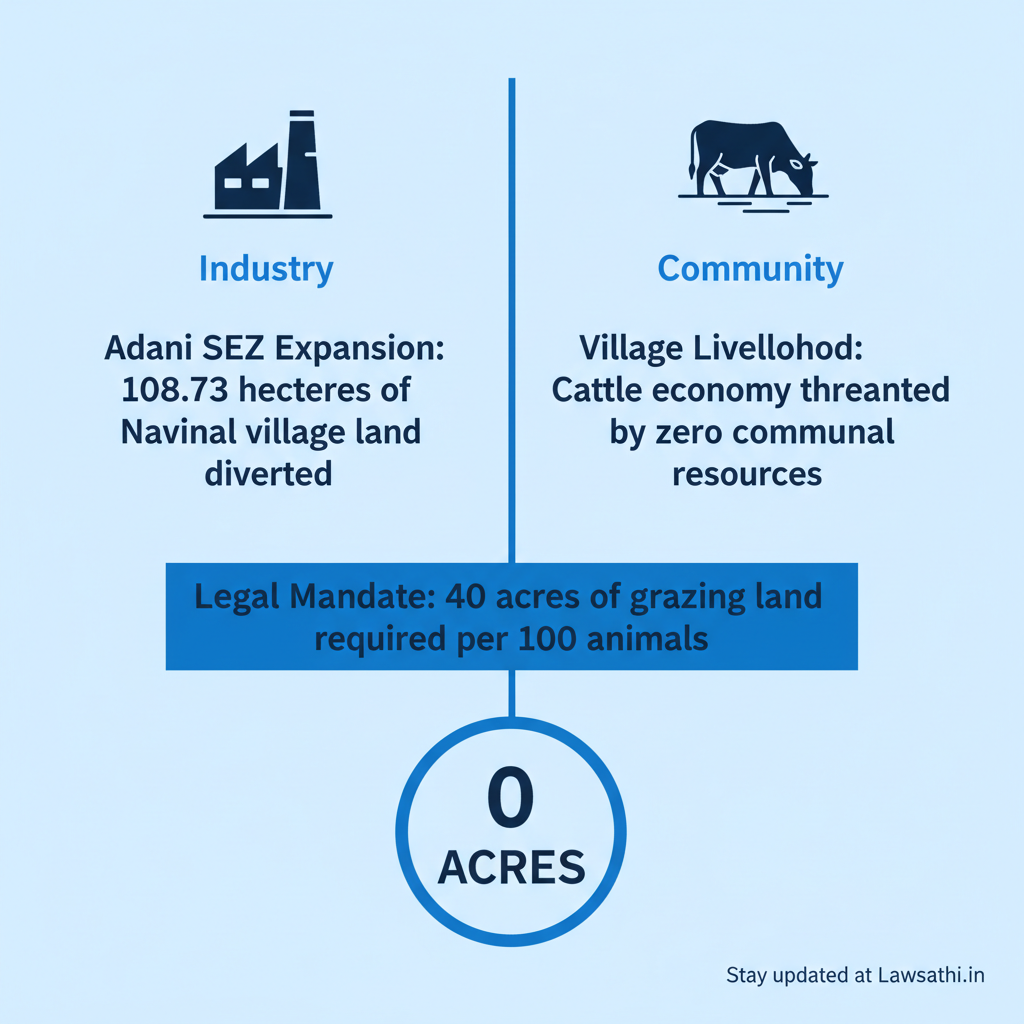

The conflict began back in 2005. At that time, the Gujarat government allotted massive tracts of land for industrial growth. Specifically, 108.73 hectares of Gauchar (grazing) land in Navinal village was diverted. This land went to the SEZ. Consequently, the villagers lost access to essential communal resources for their livestock.

Industrial Growth vs. Community Rights

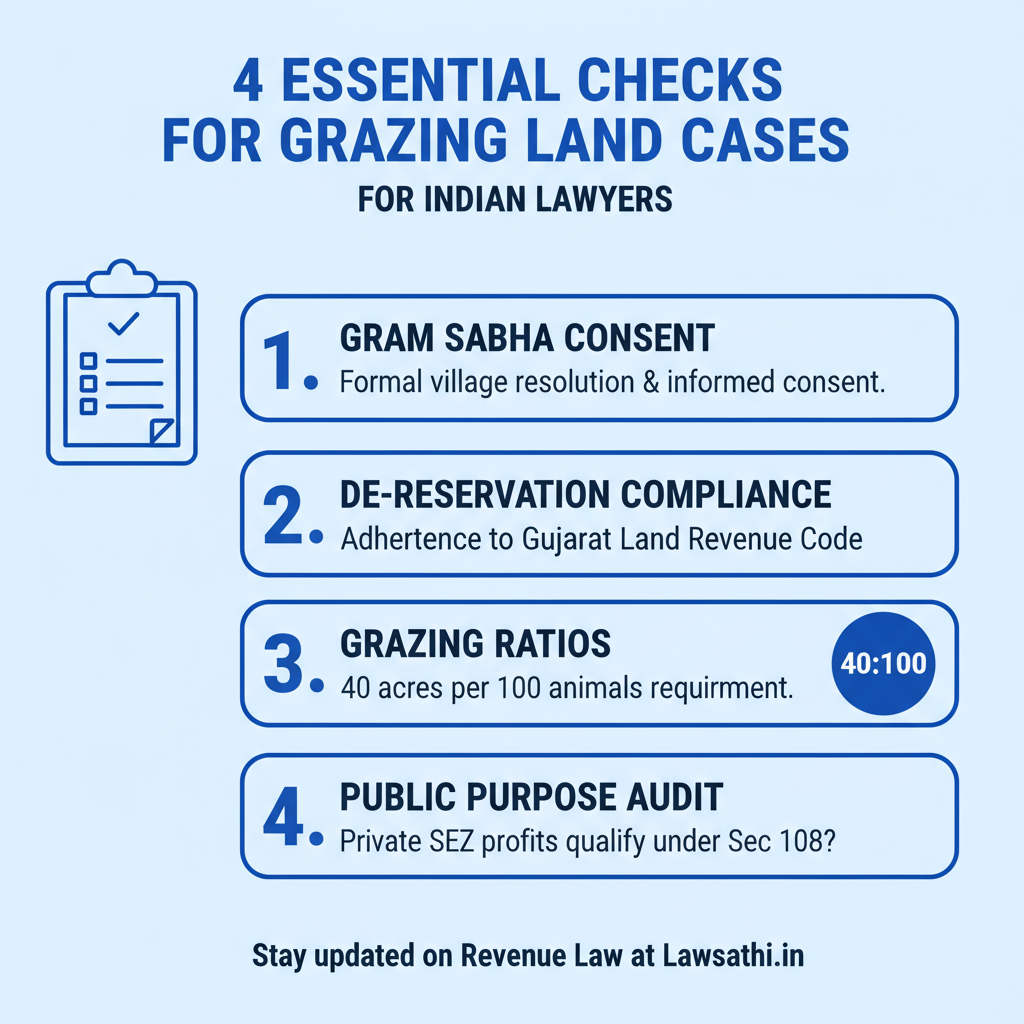

For many years, the residents of Navinal have fought to protect their livelihood. They argue that the land allotment left them with zero communal resources. Most importantly, the diversion violated the mandatory state ratio.

This rule requires 40 acres of grazing land for every 100 animals. Therefore, the industrial expansion directly threatened the local cattle economy. In contrast, the state prioritized the development of the special economic zone.

The Gujarat High Court Ruling: Why it was Challenged

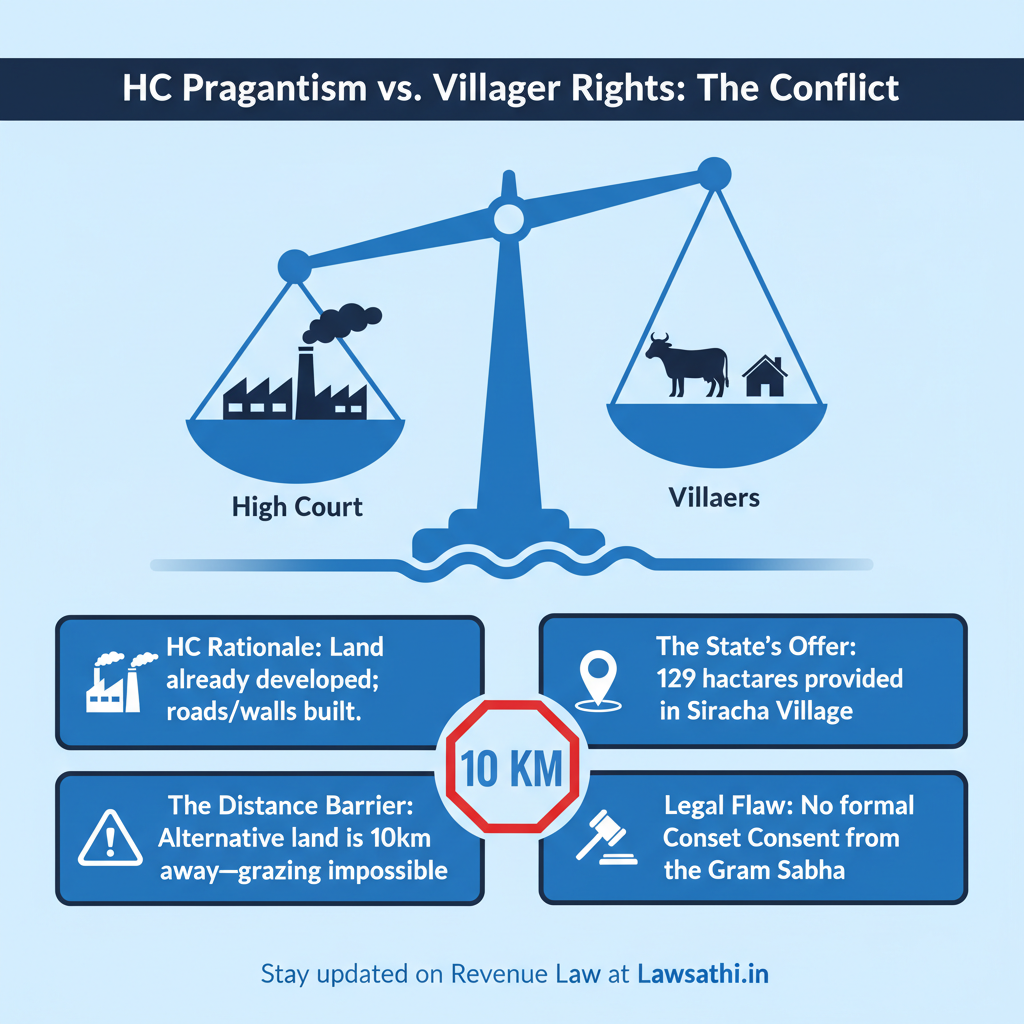

In July 2024, the Gujarat High Court attempted to resolve this long-standing friction. The court looked for a “pragmatic” solution. It aimed to balance industry and agriculture. Ultimately, the Bench allowed the state to regularize the land’s industrial status. However, this decision faced immediate backlash from the local community.

Rationale Behind the High Court Decision

The state government argued that the disputed land was already developed. For example, the SEZ had already built roads and boundary walls on the site. As a result, the High Court accepted the state’s offer of “alternative land.”

This alternative plot consisted of 129 hectares. It was located in the neighboring village of Siracha. You can find more about the Gujarat High Court weekly summary here.

Why Villagers Appealed to the Apex Court

The villagers were not satisfied with this swap for several reasons. First, the new land was located nearly 10 kilometers away. This distance made daily grazing nearly impossible for the cattle.

Second, the petitioners argued that the Gujarat Panchayat Act was not followed. Specifically, they claimed the Gram Sabha never gave formal consent. Therefore, they felt the rights of the village were ignored.

Supreme Court’s Intervention: Key Legal Arguments

The Adani grazing land Supreme Court case reached a turning point in early 2026. A Bench led by Justice B.R. Gavai issued a stay. This stay halted the High Court’s directions immediately.

This intervention highlights the court’s concern over communal land management. In fact, the court emphasized that Gauchar land cannot be used contrary to its purpose easily. Strict compliance is required for such changes.

Protecting Village Ecology

The Supreme Court noted that grazing land is vital for rural ecology. Therefore, the state cannot treat it as a mere commodity. For instance, swapping local land for distant plots undermines rights. Specifically, it affects the community’s right to life. Additionally, the Bench questioned the state’s failure to maintain minimum grazing ratios.

Timing of Compensation Policies

Furthermore, the Court analyzed the “land for land” policy. It observed that compensation should happen before industrial diversion. In this case, the state offered alternative land over a decade late. Consequently, the SC felt a stay was necessary. This helps prevent further injustice to the Navinal villagers.

Navinal Villagers’ Decade-Long Battle: A Revenue Law Perspective

This legal journey began with a 2011 PIL and has lasted fifteen years. From a revenue law standpoint, the case revolves around Section 108. This is a key part of the Gujarat Panchayat Act.

This section states that land vested in a Panchayat can be resumed only for “public purpose.” However, the villagers argue that private SEZ profit is different. Specifically, they claim it does not qualify as a public purpose.

The Legal Role of the Gram Sabha

Practice management for revenue lawyers often involves checking local consent. In this case, the Gram Sabha’s sovereignty is a major technical argument. The petitioners claim that the conversion of grazing land was illegal.

This is because there was no formal village resolution. Therefore, the lack of a “de-reservation” process makes the allotment flawed. In fact, the 2005 decision may be procedurally void.

Technical Breaks in the Revenue Chain

Specifically, the Gujarat Land Revenue Code requires strict steps. These steps apply to land classification changes. If the state bypasses these steps, the allotment remains vulnerable.

For example, the Navinal case shows how simple lapses cause problems. A single procedural error can lead to decades of court battles. Moreover, it creates uncertainty for all parties involved.

Broader Implications for Revenue Law Practitioners

The stay in the Adani grazing land Supreme Court case sends a clear signal. It reminds practitioners that the 2011 Jagpal Singh vs. State of Punjab precedent remains strong.

That ruling protects village common lands from encroachment. It also prevents easy “regularization.” Consequently, even state-backed industrial projects must undergo audits. These must be rigorous land-use audits to ensure legality.

Understanding the Public Trust Doctrine

Lawyers should remember that the state acts as a trustee. While the government “owns” the land, it is “vested” in the Panchayat. This land is held for the benefit of the people.

Therefore, any transfer to a private entity must meet high standards. Transparency is absolutely necessary in these transactions. Moreover, practitioners must evaluate if the “Public Trust Doctrine” is being upheld.

Tips for Representing Local Bodies

First, always verify if the Gram Sabha gave informed consent. Second, check if the minimum grazing ratio is maintained. You should look directly at the revenue records.

Third, ensure that land relocation plans are geographically viable. These steps are crucial when representing local bodies. They help protect villagers against large industrial corporations.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead for the Gujarat Land Dispute

The Supreme Court stay has frozen further construction on the land. This provides temporary relief for the Navinal ecosystem. However, a final hearing will soon determine the permanent status. The court may eventually mandate that the state find land inside the village.

The outcome of this case will set a major standard for Indian law. It will balance the “Ease of Doing Business” with the “Right to Life.” Revenue lawyers must watch this case closely. It provides a blueprint for challenging illegal land diversions across India.

Streamline your revenue case research with LawSathi’s AI-powered practice management. Manage complex land litigations with ease. Start your free trial today!