The legal landscape of road accidents in India has undergone a massive transformation. As we navigate the year 2026, the BNS Section 106(2) Supreme Court ruling remains a central debate. This debate involves both lawyers and drivers.

Moreover, the shift from the Indian Penal Code (IPC) to the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) is significant. This represents more than just a name change. In fact, it introduces a rigorous reporting framework. This framework directly impacts a driver’s liberty following a fatal accident.

Introduction: The 2026 Judicial Landscape of BNS Section 106(2)

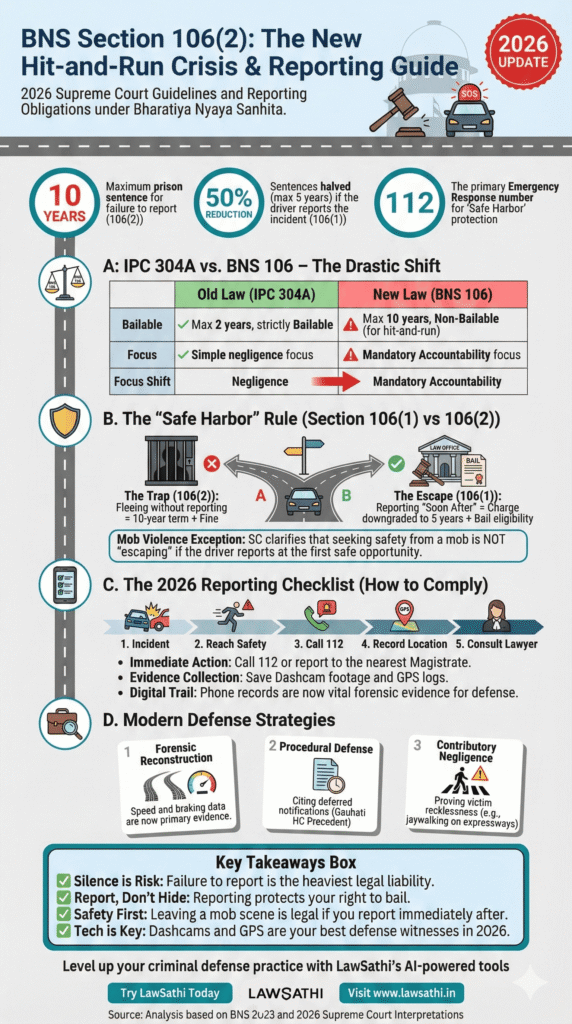

The transition from Section 304A of the IPC to Section 106 of the BNS has changed negligence laws. Previously, causing death by negligence carried a maximum of two years in prison. However, the new law significantly increases these penalties.

Modern Penalties for Criminal Negligence

Consequently, the legal community has closely watched the Supreme Court for clarifications. Specifically, experts want to know how these tougher rules apply in real-world scenarios. Furthermore, the judicial focus has shifted toward stricter enforcement of driver accountability.

Socio-Legal Context and Evolution

The implementation of hit-and-run laws faced early resistance. For example, nationwide transport strikes in 2024 forced a temporary pause on several provisions. By 2026, we see a more settled yet complex judicial environment.

Balancing Safety and Driver Rights

Courts are now balancing the need for road safety. Similarly, they must protect drivers from mob violence. This balance is critical because the new law demands immediate action. Therefore, a driver must act quickly after an incident occurs.

Current Implementation Status in 2026

Surprisingly, certain parts of the hit-and-run law remain in a unique state in early 2026. The Gauhati High Court has previously directed police not to register certain FIRs. Specifically, they flagged Section 106(2) because the notification was deferred.

Therefore, practitioners must check the latest Ministry of Home Affairs notifications daily. This technicality creates a vital defense path for those accused. As a result, many “hit-and-run” charges are being challenged on procedural grounds.

Deconstructing Section 106: Negligent Act vs. Failure to Report

Section 106 is divided into two distinct parts with very different consequences. First, Section 106(1) deals with causing death by any rash or negligent act. This carries a prison term of up to five years.

Comparing Penalties for Fleeing the Scene

Second, Section 106(2) specifically targets hit-and-run cases. If a driver flees without reporting the matter to a police officer, the penalty jumps. Specifically, the jail term can reach ten years. Furthermore, the driver must report the incident to a Magistrate to avoid these harsher terms.

Understanding the Reporting Trigger

The “reporting trigger” is the most significant change for 2026. A driver must report the incident “soon after” the accident occurs. However, the law does not define “soon after” in exact minutes.

Instead, the paradox of hit-and-run cases lies in the driver’s intent. If fear of a mob causes a delay, the courts may view the situation differently. Consequently, judges must evaluate the context of every delay.

Escaping the Scene vs. Fleeing for Safety

The Supreme Court has clarified that “escaping” is not the same as “seeking safety.” In many Indian road accidents, drivers face immediate threats of lynching. Therefore, a driver who leaves the spot to reach a police station is not necessarily a criminal.

Most importantly, the driver must prove they reported the matter at the earliest safe opportunity. Additionally, they must demonstrate that staying at the scene posed a genuine risk to their life. This distinction is vital for modern defense strategies.

The Supreme Court’s 2026 Interpretation: Key Legal Takeaways

The BNS Section 106(2) Supreme Court ruling has provided a “Safe Harbor” for cooperative drivers. If a driver reports the incident, the case falls under Section 106(1). As a result, the maximum potential sentence is halved.

Incentivized Compliance for Drivers

This creates a strong legal incentive for drivers to assist the law. In other words, reporting is better than hiding. Additionally, this shift aims to ensure victims receive faster medical attention.

Constitutional Challenges to Section 106(2)

Many legal experts have challenged the dilemma of Section 106(2) on constitutional grounds. They argue that forcing a driver to report violates Article 20(3). This article protects the right against self-incrimination.

However, the courts have generally upheld the provision. They argue that reporting an accident is a regulatory duty. In contrast, they do not view it as a forced confession of guilt. Therefore, the duty to inform remains a valid legal requirement.

Standard of Proof and Judicial Stance

Furthermore, the standard of proof for “rashness” has become more stringent. In 2026, judges often require forensic evidence to prove criminal negligence. Bare witness testimony is often insufficient for a 10-year conviction.

Consequently, the prosecution must show that the driver’s conduct was reckless. They must prove it was a total departure from the standard of a reasonable person. Finally, forensic data has become the primary tool for determining actual guilt.

Reporting Obligations: Guidelines for Drivers and Legal Practitioners

Knowing how to report is crucial for survival in the legal system. First, the driver should call the Emergency Response Support System (112) immediately. Second, they should document their location if they must leave the scene for safety.

Leveraging Digital Paper Trails

These steps provide a digital paper trail. This trail is hard to dispute in court. Additionally, it shows the driver’s willingness to comply with the law. Therefore, digital records are now a driver’s best friend.

The Role of Digital Evidence

Technology has simplified the process of proving “immediate reporting.” For example, GPS tracking and dashcam footage are now vital pieces of evidence. Additionally, lawyers can use phone records to show the timeline of the driver’s actions.

If the driver made a call to the police within minutes, the charge often fails. As a result, Section 106(2) is frequently downgraded to the lesser charge of 106(1). This reduction is a major victory for the defense.

Legal Immunity and Mitigation

While reporting does not grant total immunity, it offers substantial mitigation. A driver who reports usually remains eligible for bail under Section 106(1). In contrast, those charged under 106(2) face a non-bailable perception.

Therefore, lawyers must advise clients to prioritize the reporting obligation. Above all else, reporting must happen quickly. This action changes the entire trajectory of the criminal case.

Comparative Analysis: IPC 304A vs. BNS 106(2)

The shift from the IPC to the BNS is more than a change in numbers. The nature of the offense has shifted from bailable to potentially non-bailable. Additionally, the impact on insurance claims has changed significantly.

Insurance and Statistical Trends

Insurance companies now look for reporting compliance before processing claims. For example, failing to report may result in a rejected payout. Consequently, the financial risk is now as high as the legal risk.

| Feature | IPC Section 304A | BNS Section 106(1) | BNS Section 106(2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Punishment | 2 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years |

| Nature | Bailable | Generally Bailable | Non-Bailable (Proposed) |

| Reporting Duty | Not a term condition | Aids in bail | Mandatory for leniency |

| 2026 Status | Repealed | In Force | Awaiting full notification |

Statistical Impact on Road Safety

Since the introduction of the BNS, road safety statistics show higher reporting rates. This trend suggests that the threat of a 10-year term works as a deterrent.

However, critics argue it leads to police corruption. Specifically, they fear police might misuse the threat of 106(2) to extort drivers. Therefore, proper legal oversight remains essential.

Defense Strategies for Lawyers in BNS Hit-and-Run Cases

Lawyers must adapt to the evidentiary standards of 2026. One effective strategy is leveraging the “Fear of Mob Violence.” If the defense can show a credible threat, reporting delays become justifiable.

Procedural Defense Tactics

Furthermore, challenging the “rashness” element through accident reconstruction is becoming common. Additionally, procedural defenses are highly effective right now. For instance, citing the Gauhati High Court’s ruling on Section 106(2) can help quash FIRs.

If the provision is not yet officially in force, the police cannot use it. Therefore, checking local notifications is the first step in any defense. This strategy has already saved many drivers from unfair prosecution.

Dealing with Forensic Accident Reconstruction

Most importantly, defense lawyers should collaborate with forensic experts. In 2026, many cases are won by proving contributory negligence. For example, the victim may have been walking on a high-speed expressway.

In such cases, the driver’s “rashness” is put into question. Specifically, forensic data can prove speed limits and braking distances. These facts help to clear the driver’s name and reduce the charges.

Conclusion: The Future of Road Negligence Laws in India

The BNS Section 106(2) Supreme Court ruling has defined the path for road safety. It balances the victim’s right to justice with the driver’s right to a fair trial. By 2026, the law has made one thing clear.

Specifically, silence is the biggest risk for a driver. Reporting an accident is no longer just a moral duty. Instead, it is a primary legal defense.

Summary of the Balanced Approach

The courts continue to refine these rules to prevent misuse. While the penalties are harsher, the “Safe Harbor” of reporting remains a vital protection. For legal practitioners, staying updated is essential.

Above all, the focus has shifted toward accountability through reporting. Stay ahead of the latest BNS interpretations with LawSathi’s AI-powered tools. Try LawSathi today to streamline your criminal defense practice.