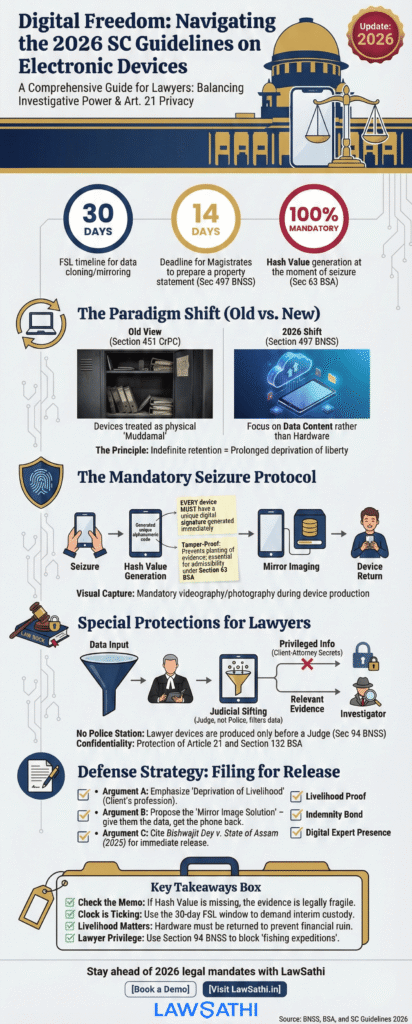

The year 2026 marks a historic shift in how Indian courts handle digital evidence. For years, police agencies treated mobile phones and laptops like any other physical “Muddamal.” However, the Supreme Court has now recognized that our devices are extensions of our very selves.

As a result, the old practice of keeping devices in police lockers for years is ending. New judicial mandates now balance investigative needs with fundamental privacy rights. Specifically, lawyers must understand these changes to protect their clients’ data and professional secrets. This guide explores the latest rules for the interim custody of electronic devices in the modern legal era.

Introduction: The Shift in Digital Evidence Jurisprudence in 2026

Indian jurisprudence has evolved from focusing on physical property to prioritizing data-centric rights. In late 2025, the Supreme Court solidified this transition in landmark rulings. These decisions emphasize that electronic devices are not just plastic and silicon.

Moreover, they are high-volume repositories of a person’s entire life. Consequently, the judiciary now treats these devices with a higher degree of protection.

Beyond Physical Property

Previously, courts applied Section 451 of the CrPC to all seized items equally. Now, the judiciary distinguishes between the physical hardware and the digital content within.

For example, recent directions in In Re: Summoning Advocates SMW(Crl) 2/2025 highlight this important distinction. In fact, judges now focus on the data rather than the device itself.

Modern Legal Standards

Consequently, electronic devices require a different legal standard than weapons or vehicles. The court now views indefinite retention as a “prolonged deprivation of liberty.”

Therefore, the focus has shifted toward returning the physical device after securing a digital clone. This ensures that the owner’s livelihood remains unaffected during the trial. Furthermore, it prevents the unnecessary aging of expensive hardware.

The Core Conflict: Investigative Necessity vs. Art. 21 Privacy Rights

The primary challenge lies in balancing police powers with its Right to Privacy. Under the Puttaswamy judgment, every citizen enjoys a right to digital privacy. Investigating agencies often argue that they need full access to solve crimes.

However, the Supreme Court recently ruled that investigative power is not an “absolute license to browse.” This limits how much data an officer can inspect during an arrest.

The Right to Digital Privacy

Furthermore, the “Right to be Forgotten” has gained significant traction in 2026. Therefore, police cannot hold irrelevant personal data indefinitely.

In fact, keeping a device for months without a clear forensic need violates Article 21. Courts now demand a high level of “proportionality” when agencies seize digital tools. As a result, the state must justify every day of custody.

Data Mirroring as an Alternative

Consequently, “Data Mirroring” has become the preferred legal alternative to physical custody. For example, the Delhi High Court in Rakesh Kumar Gupta v. DRI held that agencies should clone data rather than retain hardware.

This process allows the police to keep the evidence. At the same time, the owner keeps their phone. Therefore, the investigation proceeds without disrupting the citizen’s daily life.

Mandatory Procedures for Seizure and Interim Release

The 2026 guidelines introduce strict procedural safeguards during the seizure process. First, the investigating officer must create a “Hash Value” at the very moment of seizure. This unique digital signature acts as a tamper-proof seal for the data. Most importantly, it prevents the planting of evidence.

The Hash Value Mandate

Additionally, Section 63 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam (BSA) now makes the Hash Value mandatory. Without this value, the admissibility of the digital record becomes highly questionable.

Consequently, lawyers should always check the seizure memo for this specific alphanumeric code. If the code is missing, the evidence may be excluded. In other words, procedural compliance is now vital for a successful prosecution.

Timelines for Forensic Extraction

Second, the Forensic Science Laboratory (FSL) must now follow strict timelines. Under the new protocols, cloning should ideally happen within 30 days.

Specifically, Section 497 of the BNSS gives Magistrates power to order quick disposal. Therefore, if the FSL delays mirroring, the defense can move for immediate interim custody of electronic devices. This creates a sense of urgency for forensic examiners.

Navigating the New BNSS Framework for Electronic Records

The transition from the CrPC to the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) has changed the game. Section 451 of the old CrPC is now replaced by Section 497 of the BNSS. This new provision is much more aggressive regarding timelines and judicial accountability.

Section 497 BNSS Protocols

Specifically, the Magistrate must now prepare a statement of the property within 14 days. Additionally, a photograph or videograph of the device is mandatory during production.

As a result, the court has a clear 30-day window to decide on the interim release. This change aims to reduce the massive backlog of seized electronics. Furthermore, it prevents devices from rotting in police godowns for years.

Judicial Oversight and Speaking Orders

Moreover, Magistrates can no longer pass “mechanical orders” to keep devices in custody. In 2026, the court must issue a “Speaking Order” if it refuses to return a phone.

For instance, Karnataka High Court guidelines emphasize that trial courts must facilitate the “cloning and return” protocol. This ensures that the digital evidence is preserved. Furthermore, it ensures the hardware is released quickly.

Privileged Communications: Protecting Lawyer-Client Confidentiality

The Supreme Court has introduced revolutionary protections for legal professionals in 2026. These rules prevent the police from “fishing” through an advocate’s digital files. Above all, the court recognizes that a lawyer’s phone contains sensitive client secrets. These secrets are protected by law and professional ethics.

Safeguards for Seized Advocate Devices

If an officer summons a lawyer’s device under Section 94 of the BNSS, the lawyer does not go to the police station. Instead, the Supreme Court mandates that the device be produced only before a judge.

This prevents unauthorized police access to privileged communication. Consequently, it protects the bond between a lawyer and their clients. In fact, this rule is a major victory for the legal fraternity.

The Judicial Sifting Process

Additionally, the court must now perform “Judicial Sifting.” This means the judge examines the device to exclude confidential client data.

For example, Section 132 of the BSA protects these communications from disclosure. Therefore, investigators can only access files specifically related to the alleged crime. As a result, the rest of the lawyer’s digital life remains private.

Practical Strategies for Defense Counsel: Filing for Interim Release

When applying for the interim custody of electronic devices, your drafting must be precise. First, emphasize the “deprivation of livelihood” caused by the seizure. For many professionals, a laptop is an essential tool.

Consequently, its absence can cause irreparable financial harm. You must highlight this loss to the Magistrate. Additionally, provide proof of the client’s occupation to strengthen the case.

Drafting an Effective Application

Second, always propose the “Mirror Image” solution in your petition. Tell the court that the police have already had sufficient time to clone the data.

Furthermore, rely on Bishwajit Dey v. State of Assam (2025) to argue for immediate release. You may offer to provide an indemnity bond as security. This approach shows you are willing to cooperate with the court.

Ensuring Data Integrity

Finally, request the presence of a digital expert during the hashing process. This ensures that the police do not accidentally—or intentionally—alter the metadata.

In fact, providing a “Mirror Image” to the Court yourself can speed up the process. Most importantly, make sure the Investigating Officer signs the final Hash Value. Do this before the device is released to your client to avoid future disputes.

Conclusion: The Future of Digital Forensics and Law

The 2026 Supreme Court guidelines have finally brought Indian law into the digital age. By moving away from physical retention, the courts are protecting both trials and privacy. These rules ensure that investigations remain ethical and targeted. Essentially, the “Digital First” approach is making the criminal justice system more efficient.

Therefore, the mandatory use of Hash Values will lead to faster trials. Additionally, the new protections for lawyers safeguard the sanctity of the legal profession. As we embrace the BNSS and BSA framework, staying updated is vital. Every practitioner must master these procedural nuances to succeed.

Stay ahead of the latest Supreme Court mandates with LawSathi’s AI-powered legal updates. Streamline your case research and manage digital evidence logs effortlessly. Book a demo today.