The legal battle regarding the Azhikode assembly constituency has finally reached a definitive conclusion. Specifically, the recent KM Shaji Supreme Court judgment has clarified the high evidentiary bar required to unseat an elected representative.

Furthermore, this ruling provides a vital shield for legislators against unproven allegations of electoral misconduct. In short, the court has prioritized the sanctity of the democratic mandate over circumstantial claims.

Introduction: The Finality of the KM Shaji Disqualification Dispute

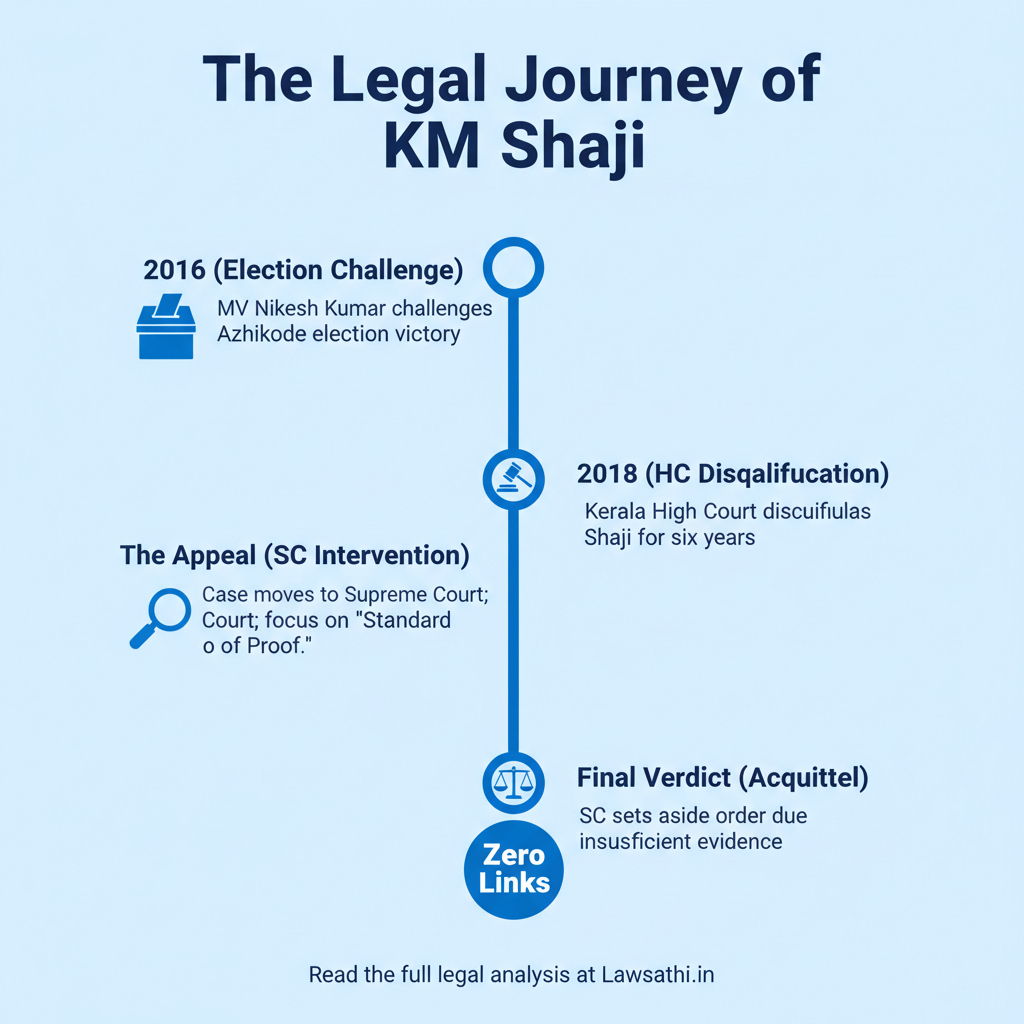

The Supreme Court recently set aside the 2018 Kerala High Court order. This original order had disqualified former MLA KM Shaji. Originally, the High Court found Shaji guilty of using communal tactics during his 2016 election campaign.

However, the apex court has now overturned this decision. Consequently, this case marks a significant movement for Indian election law. It emphasizes that a candidate’s victory is not easily undone.

A Long Road from the High Court

The dispute began after the 2016 assembly elections in Kerala. Rival candidate MV Nikesh Kumar challenged Shaji’s victory in the Azhikode constituency. He alleged that Shaji used religious appeals to secure votes.

As a result, the Kerala High Court issued an order for disqualification in November 2018. The legal journey took years to reach the final appellate stage in New Delhi.

Significance for Election Law

This ruling is highly significant for legal practitioners. Specifically, it addresses the burden of proof in cases involving “corrupt practices.” Most importantly, the court emphasized that election petitions are quasi-criminal in nature. Therefore, the evidence must be beyond reasonable doubt. In other words, suspicion is not a substitute for facts.

Case Background: The Allegations of Corrupt Practices

The legal challenge primarily focused on “corrupt practices” under the Representation of the People Act, 1951. MV Nikesh Kumar, the petitioner, claimed that Shaji’s campaign distributed communal leaflets.

These materials allegedly urged voters not to support a “non-Muslim” candidate. According to the petitioner, this action violated the secular spirit of Indian elections.

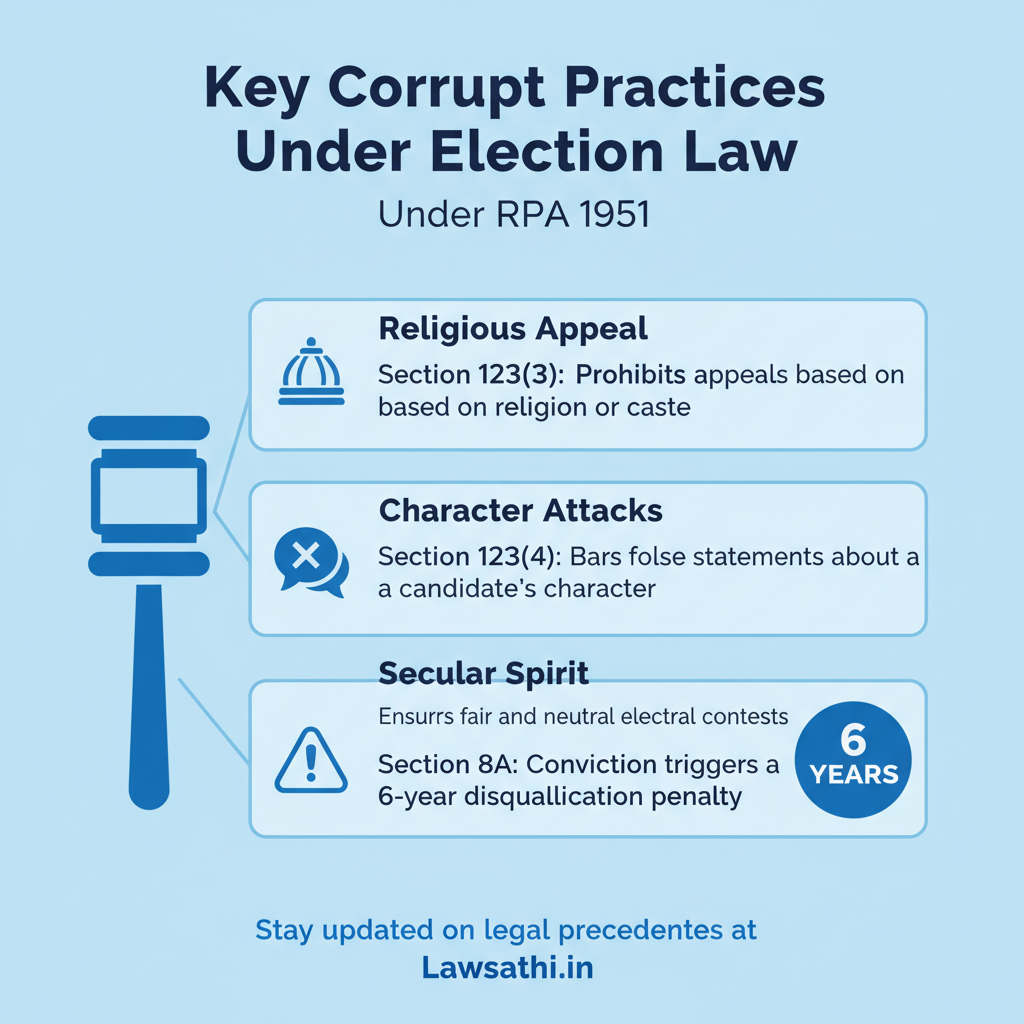

Breaking Down Section 123(3)

The allegations fell under Section 123(3) of the Representation of the People Act. This section prohibits appeals by a candidate based on religion or caste. If proven, such an appeal constitutes a corrupt practice.

Furthermore, Section 123(4) deals with false statements about a candidate’s personal character. Both sections aim to keep electoral contests fair and neutral.

The Problematic Pamphlets

The central piece of evidence was a leaflet found near the constituency. According to the petitioner, these pamphlets were used to polarize the electorate. He argued that Shaji actively encouraged this religious divide.

As a result, the petition sought to nullify the entire election result. However, the origin of these papers remained a point of heavy legal debate.

The Kerala High Court’s 2018 Reasoning

In its initial ruling, the Kerala High Court took a stringent view of the evidence. Justice PD Rajan observed that the pamphlets created a clear religious divide.

Consequently, the court disqualified KM Shaji from contesting any election for six years. This was a severe penalty that halted his active political career.

Declaring the Runner-up as Winner

Initially, the High Court intended to declare the runner-up, Nikesh Kumar, as the winner. However, this part of the order faced immediate legal hurdles. Historically, courts rarely declare a runner-up as the winner unless the “but for” rule is satisfied.

Specifically, this means the petitioner must prove they would have won if the corrupt practice never occurred. This is a very difficult standard to meet in a multi-candidate race.

Findings on Religious Materials

The High Court focused on the dissemination of religious materials during the campaign. It found that the material was designed to exploit communal sentiments. Therefore, the court held that such actions undermined the purity of the electoral process.

This led to the strict disqualification order under Section 8A of the Act. For a time, it seemed the evidence was sufficient for a permanent ban.

Supreme Court Intervention: Key Legal Arguments

When the case reached the Supreme Court, the focus shifted to the “standard of proof.” Shaji’s counsel argued that the High Court failed to link the leaflets to the candidate directly.

Furthermore, they contended that third-party propaganda should not lead to an MLA’s disqualification. In fact, they argued such a link must be proven with absolute certainty.

The Quasi-Criminal Standard

The Supreme Court reaffirmed that election petitions require a high standard of proof. For example, the Jagannath v. Narayan Uttamrao Deshmukh case established that the onus is strictly on the petitioner.

Moreover, suspicion alone cannot replace legal proof in these sensitive matters. Because the consequences are severe, the evidence must be robust.

Proving Candidate Consent

A major point of contention was whether Shaji consented to the leaflets. Under Section 123, a candidate is only liable for acts done with their knowledge or consent. However, the evidence in this case was largely circumstantial.

For instance, the mere recovery of leaflets from a public place does not prove a candidate’s involvement. Therefore, the court found the chain of evidence broken.

The Verdict: Why the SC Set Aside the Disqualification

The final KM Shaji Supreme Court judgment concluded that the evidence was insufficient. The Bench observed that the link between the candidate and the communal material was weak. Consequently, the court set aside the six-year disqualification. Shaji was thus cleared of the charges.

Distinction Between Supporters and Candidates

The Court highlighted a vital distinction in election law. Specifically, it distinguished between the independent actions of supporters and the authorized actions of the candidate.

While supporters might use distasteful rhetoric, the candidate is not automatically responsible. Therefore, proving direct authorization is essential for any disqualification. Without this link, no candidate can be safely unseated.

Strict Construction of Penal Provisions

Moreover, the Court emphasized the need for “strict construction” of Section 123. Because these provisions result in disenfranchisement, they must be interpreted narrowly.

If the evidence is not watertight, the court must favor the elected mandate. Finally, this protects the will of the voters from being overturned by weak claims.

Impact on Indian Election Jurisprudence

This ruling sets a strong precedent for future election disputes in India. It reminds petitioners that they must provide a concrete “paper trail.” Without it, challenging a democratic mandate is nearly impossible. Additionally, the ruling protects leaders from political vendettas.

Evolving Definitions of Corrupt Practice

As we enter a digital era, this judgment becomes even more relevant. For instance, proving “consent” for social media posts or viral messages is difficult.

Specifically, this case suggests that courts will require clear evidence before holding candidates liable for online propaganda. The principles of the PC Thomas case continue to resonate here today.

Protecting the Elected Representative

The judgment strengthens the legal position of winners in election petitions. In other words, an election result is not a fragile thing. It cannot be broken by unverified allegations or anonymous pamphlets. Consequently, politicians can feel more secure in their mandates if they maintain campaign compliance.

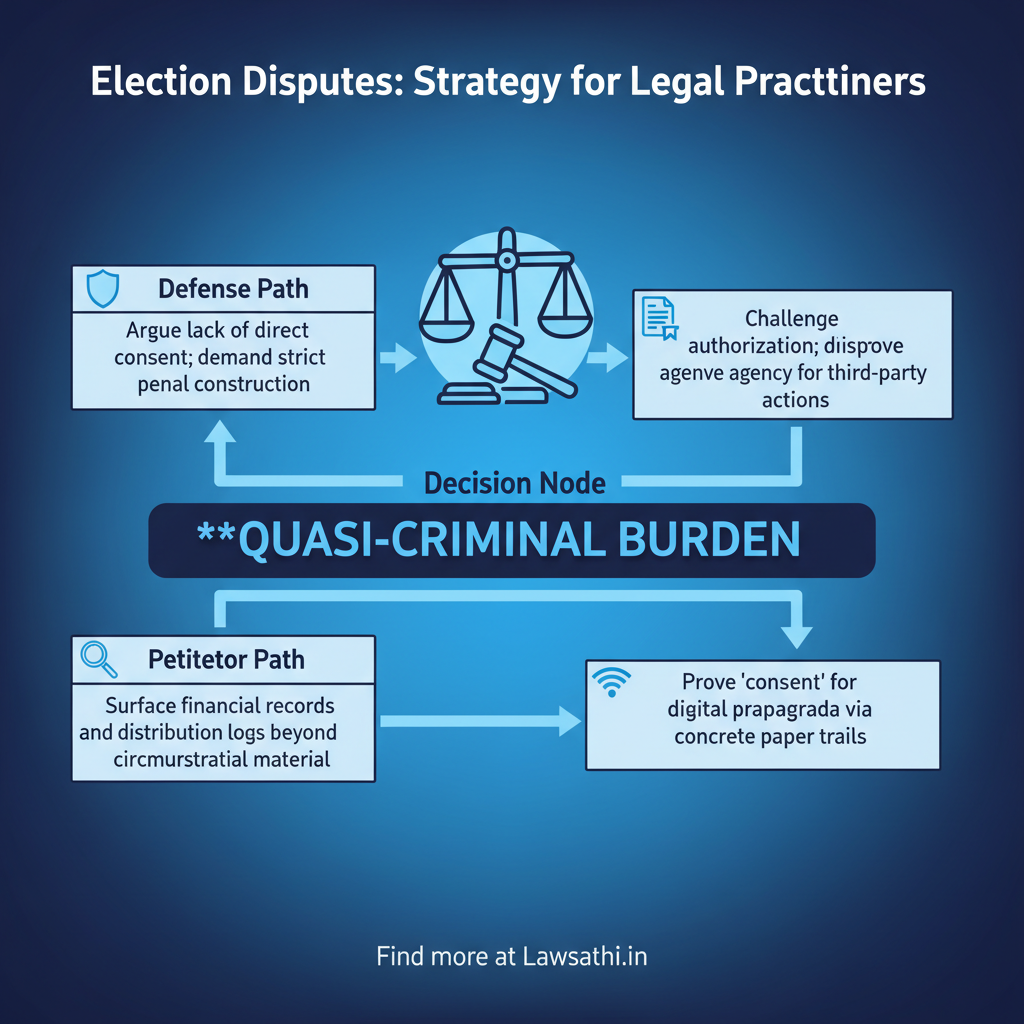

Practical Takeaways for Election Lawyers

For lawyers practicing in the High Courts and the Supreme Court, this case is a goldmine. First, always scrutinize the “agency” factor. You must ask: Did the candidate actually authorize the specific act? Second, ensure that testimonies are backed by physical evidence that links back to the election agent.

Strategies for the Defense

If you are defending an MLA, focus on the lack of direct consent. For example, argue that fringe supporters may have acted suo motu. Furthermore, use the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard to challenge the petitioner’s evidence. This strategy proved successful in the KM Shaji case.

Strategies for the Petitioner

On the other hand, if you are representing a petitioner, you need more than just offensive material. Specifically, you should aim to find financial records or distribution logs.

These records could prove that the candidate’s campaign fund paid for the communal material. Without such links, the court is likely to dismiss the petition. In conclusion, thorough investigation is the key to success.

The KM Shaji Supreme Court judgment serves as a landmark for practitioners. Above all, it balances the need for fair elections with the protection of democratic winners. As legal technology advances, analyzing these precedents becomes simpler and more efficient.

Streamline your research on landmark election law cases with LawSathi’s AI-driven legal search. Try LawSathi today to manage your practice with precision.